About Cannabis

INDICA & SATIVA

There are two main types of cannabis plants: Cannabis Indica and Cannabis Sativa, or just Indica and Sativa in short.

These two types of plants differ in several ways: origin, appearance, flowering time and yield size and effect. Cross-breeding these two types has led to a wide range of so-called hybrid strains. These hybrids can be 50/50, Indica-dominant or Sativa-dominant.

ORIGIN

Cannabis Indica is believed to have originated from the Hindu Kush region in India, Pakistan, and Afghanistan. Cannabis Sativa originates from areas around the equator like Colombia, Mexico, Thailand and Southeast Asia.

APPEARANCE

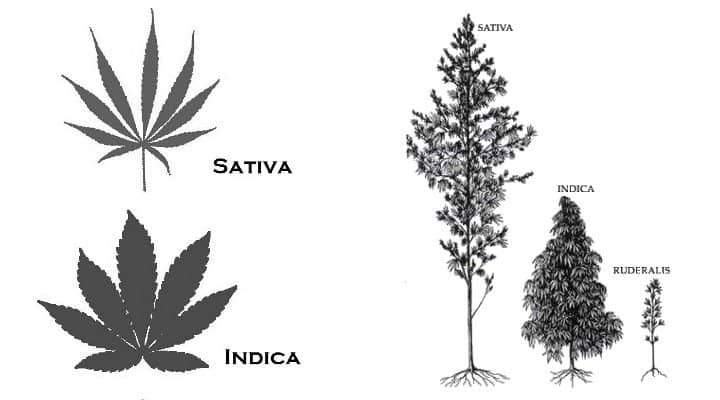

The unique appearances that both types of plants have developed because of the different geographical locations both plants appear in the wild.

First, Indica plants usually grow short and wide; its leaves are wide and short with wide and short blades. The buds of the Indica plants are also wide, dense and bulk.

Sativa plants grow tall and thin; its leaves are long with thin long blades. The buds of Sativa plants are long and thin.

FLOWERING TIME AND YIELD SIZE

While the flowering time of Indica’s is 8 to 12 weeks, Sativa’s have a flowering time of 10 to 16 weeks. Because Indica’s are smaller than Sativa’s in general, the yields of Indica’s are smaller on average as well.

EFFECT

Indica:

- Gives a body high

- Relieves pain

- Relaxes muscles, relieving spasms, seizures, and headaches

- Relieves anxiety and stress

Sativa:

- Gives a so-called cerebral high

- Gives energy and stimulates

- Up-lifting

- Increases focus and creativity

Because of this distinct contrast, Sativa strains are preferred for daytime and Indica strains for nighttime.

Popular Indica strains are White Widow, O.G. Kush, and Northern Light.

Popular Sativa strains are Purple Haze.

Ruderalis:

Now you know all about the differences between Indica and Sativa, it is time to inform you about Cannabis Ruderalis. There is still some disagreement as to whether Ruderalis is a separate species or subspecies. The characteristic that sets Ruderalis apart for other cannabis plants is its growing cycle; the transition from growing to flower period depends on the maturity of the plant and not the ratio of light/dark.

A pure Cannabis Ruderalis has low concentrations of THC, which makes her uninteresting to smoke. However, its stability, short growing cycle, and ability to start flowering automatically make her attractive to growers. The genes of the Ruderalis allows growers to create autoflowering hybrids.

THC & CBD

There are over 450 compounds in cannabis plants, 66 of them are referred to as cannabinoids, a chemical that acts on cannabinoid receptors in the human brain. This results in the alteration of neurotransmitter release. Cannabidiol (CBD) and tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) belong to the cannabinoids.

WHAT IS THC?

THC is usually referred to as the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana, meaning that it affects your brain and gets you high. After consuming cannabis, THC stimulates your brain and enhances the release of dopamine. Depending on the dose of THC it can be sedative, stimulating or psychedelic.

WHAT IS CBD?

CBD is considered a non-psychoactive compound; it will not make you high. This may sound disappointing to recreational users as they usually smoke to get high, but this unique quality of CBD is what makes CBD interesting for medical purposes. Marijuana high in CBD has been found to have significant medical benefits without making its users feel stoned.

SO WHAT’S THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THESE TWO CANNABINOIDS?

As noted above, the main difference between THC and CBD is that THC is psychoactive and CBD is non-psychoactive. In other words: THC affects your brain and gets you high while CBD won’t. CBD even has the capacity to reverse the effect of THC.

THC has been found to have the ability to make its users feel anxious; CBD has the opposite effect. It has even been shown that CBD can reduce the anxiety caused by the use of THC.

Also, THC has a wide range of effects on sleep because it works on the body’s endocannabinoid system, which is responsible for regulating sleep among other things. THC makes it easier to fall asleep, it makes you sleep longer and deeper and it enhances breathing in sleep apnea. CBD, on the other hand, has the capacity to increase alertness.

With both THC and CBD there is no risk of overdosing.